I had wanted to go to the Museum of the History of Ukraine during the Second World war in Kyiv for quite some time, but the current war always got in the way. I managed a few weeks ago, and there were many, many interesting aspects to talk about.

First of, for those unfamiliar with Kyiv, the museum itself is located under the monumental Mother Ukraine, Україна-мати, a 62m-tall (102m if you count its base) Soviet-era titanium statue built in 1979 as a war memorial. Its two sculptors were both born in Dnipro: Evhen Vuchetych, who died in 1974 and is also the designer of the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park in Berlin, and Vasyl Borodai, who completed the project.

You might have heard that Mother Ukraine got a decommunisation make-over on August 1st, 2023, when the Soviet crest, showing the hammer and the sickle, got removed to the benefit of the beloved (here) Ukrainian tryzub. Although this was years in the making, since Soviet and communist symbols were outlawed by the Ukrainian Parliament in 2015, a referendum held in July 2023 showed that an overwhelming majority of the citizens consulted were in favour of getting rid of the Soviet symbol on Mother Ukraine’s shield.

To illustrate this sentiment, my first sight upon entering the museum was that of a Ukrainian soldier giving a disdainful kick in the Soviet Crest, now exhibited in the entrance hall, but looking belittled by an immense blue and yellow flag engulfing the entire ceiling.

In the same hall, the monumental architecture is entirely subdued by Ukrainian identity. Ukraine now is reappropriating itself spaces of propaganda, and the museum of World War II is one shining example of that effort made for Ukraine to decommunize, decolonize and redefine its history from a Kyiv-centered, and no longer from a Moscow-centered perspective.

In the darkness of what used to be a Soviet architectural token, Ukraine has managed to make shine not only its beloved flag, but also its history, which it is now intent on separating from that of the agressor.

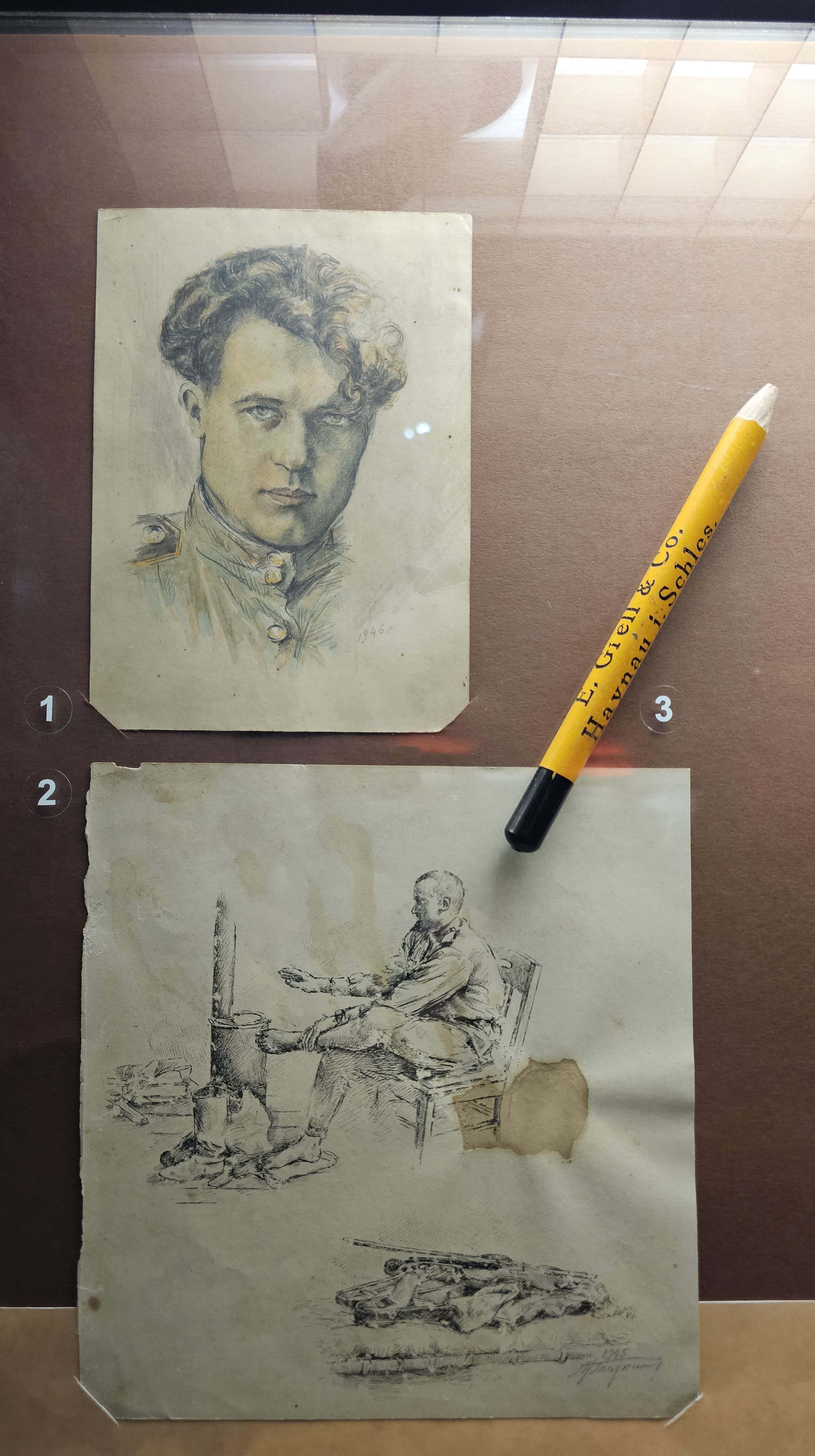

In one of the rooms, artifacts retrieved from the battleground and families’ archives give an idea of what everyday life was for a Ukrainian soldier, not unlike the possessions of soldiers currently fighting.

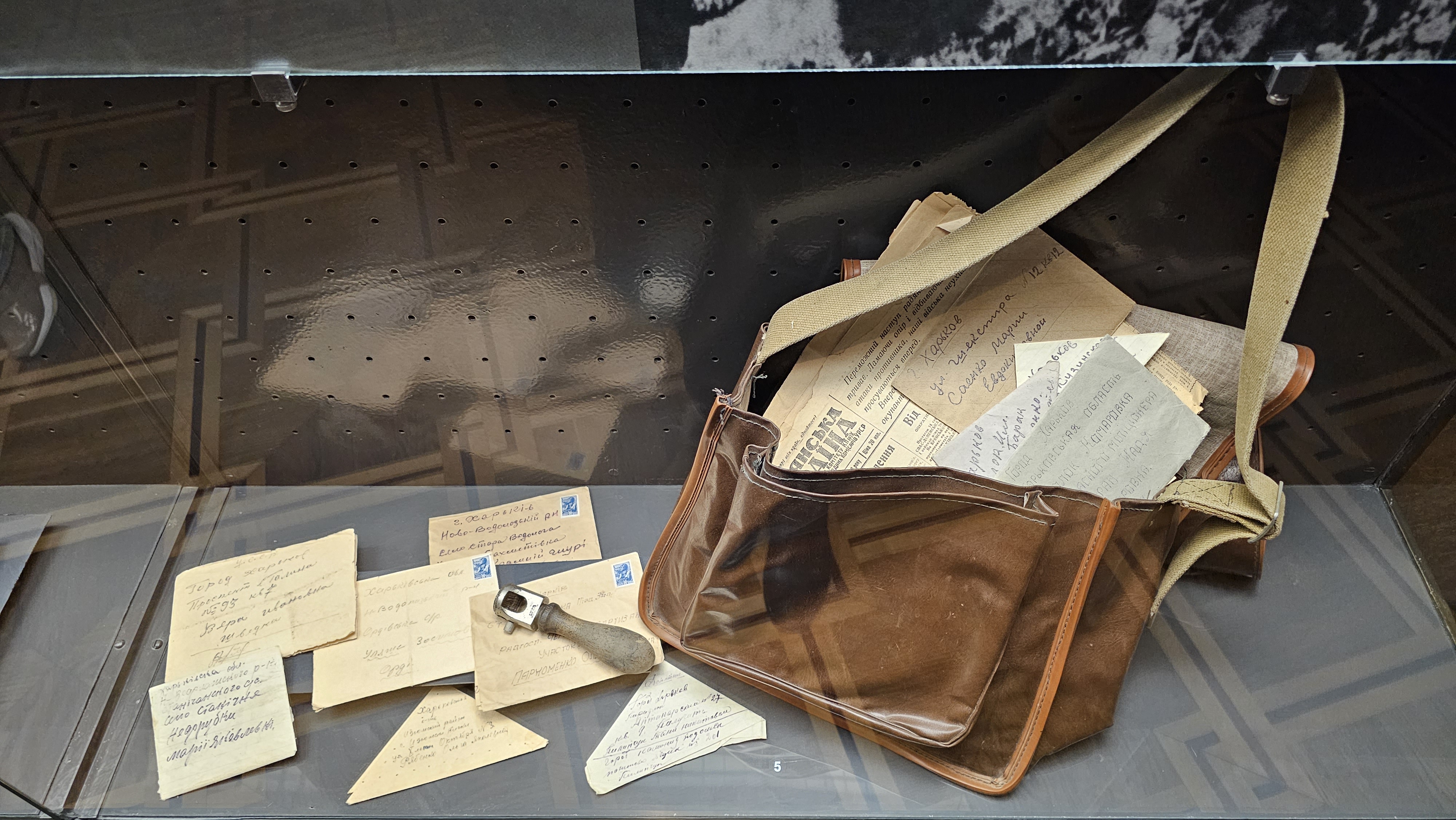

A vitrine showcases pictures of burnt cities. Kharkiv destroyed. Kyiv destroyed. Again, not unlike the current aftermaths of Russian shellings. There are also birth certificates – they emphasize the regrowth of the country. A very moving display shows a postman’s bag with letters from soldiers that never reached their recipients. They were written in Kharkiv region in June and July 1941. A team of researchers is still trying to find surviving family members and hand them over, if 80 years delayed. 660 copies of letters have been handed over to relatives, and the research continues to find recipients of the several dozens remaining.

In another room, the monumental architecture is matched by an equally monumental display of thousands of pictures retrieved from family archives: ad infinitum, “The Wall of Memory” depicts thousands of soldiers, “a collective portrait of a generation that has suffered the bloodiest war in history. There people were in different armies, under different flags, some returned and some remained lying in the soil on the land for which they fought until the very last”, reads a sign.

Along music instruments and a long banquet table where funeral letters are displayed in a macabre last supper formed by soldier’s mess tins and a few music instruments, the display is a reminder of the humanity lost in what historian of Ukraine Timothy Snyder calls “the bloodlands”.

Like a solemn reminder to contemporary Ukraine, the sign reads further: “We are the memory we keep. The attitude to human life as the highest value determines the maturity and civility of a nation. Therefore, the memory of the Ukrainian people about the war is the memory of each lost and destroyed life.”