In the very heart of Kyiv, just next to the ruins of the Tithe Church, the first religious building made in stone in the slavic world, dating back to the 10th century, you can find the monumental National Museum of the History of Ukraine. Its basement windows are still sealed with sandbags and wood panels, but its huge windows on the upper flows are rid of protection, not even showing signs of tape, generally used in times of war as a precaution to minimize the damages caused by shards, in case of explosions. Despite the war, the museum is open, but how does one speak about the history of a country, when one of its bloodiest chapters is still being written? How to make sense of the chaos in which the country sank since 2014, and even more so since February 24th, 2022? Since the beginning of the full scale invasion of Ukraine, dozens of cultural institutions, historic sites and religious buildings have had to close or displace their collections, so as to shelter a heritage that is also targeted and destroyed by bombs and by the Russian occupier.

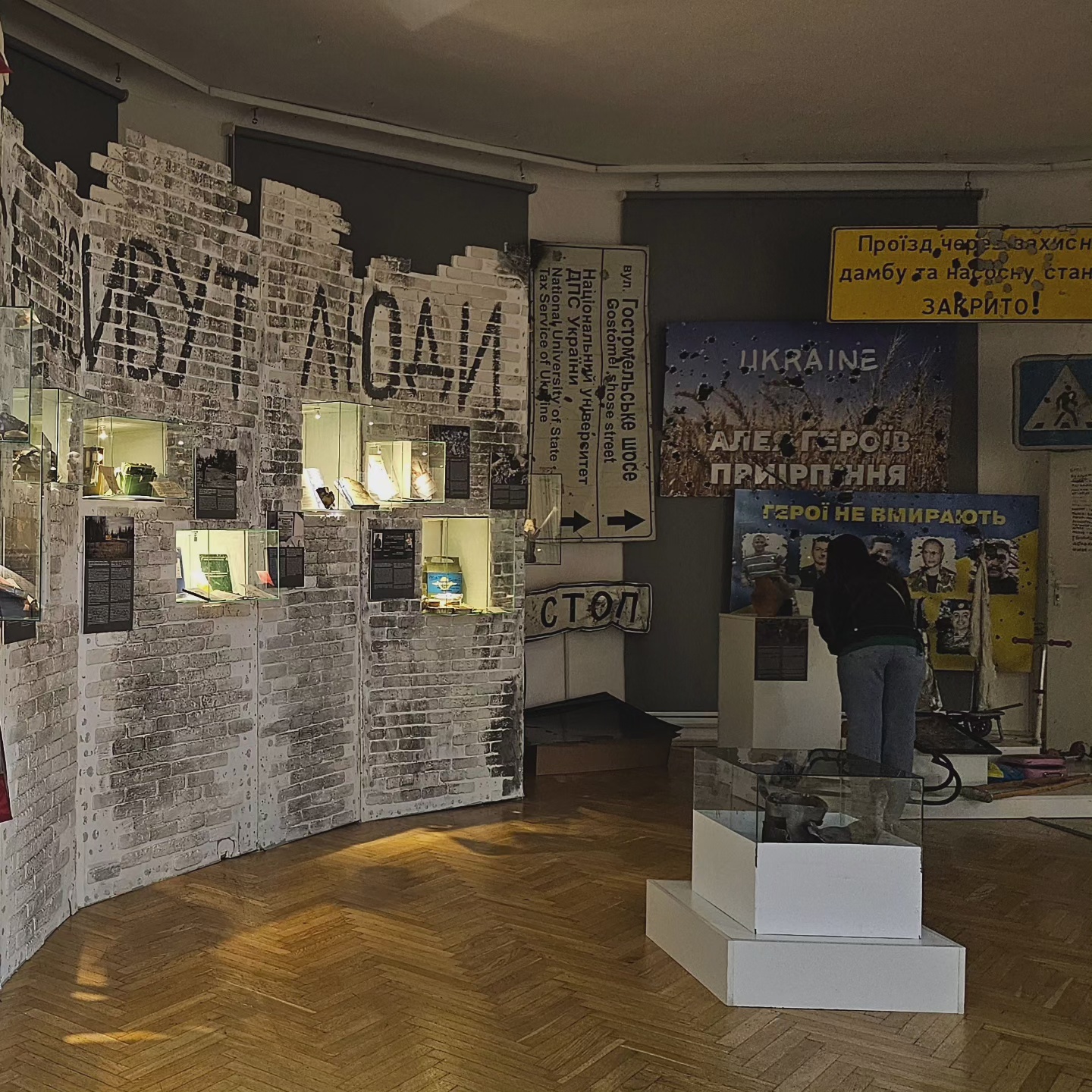

Opening a museum’s doors is thus an act of resilience, but one that can’t be done without including in the collections the very contemporary history of the country. It is the purpose of the museum itself, at a time when the identity of Ukraine is threatened to its core, and it is clear from the very start, in the entrance hall, where exhibits of the violence of the Russian agression and occupation of the Kyiv region line up in a very concrete display of what we have heard of, or seen.

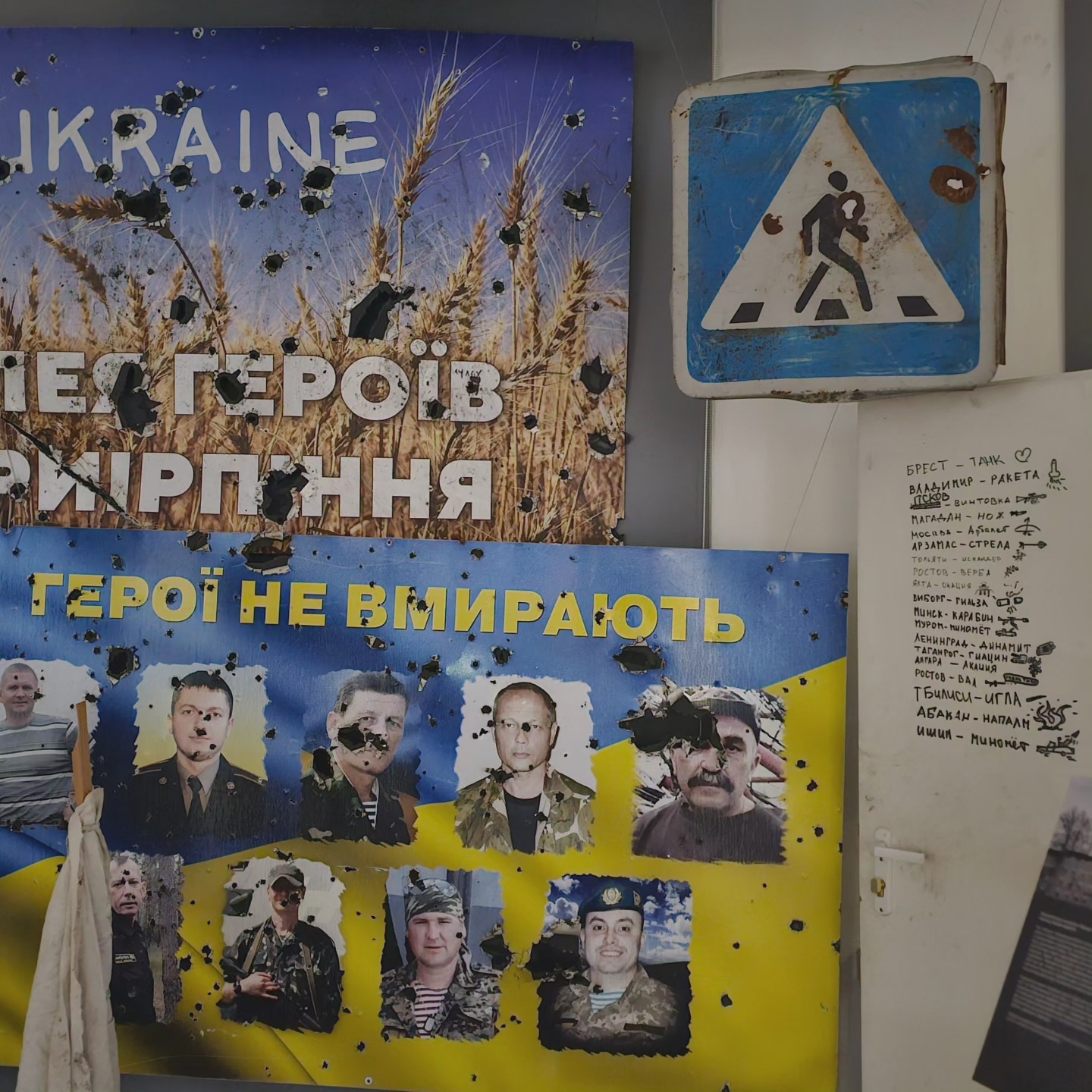

Shrapnels, rocket shells, bloodied stretchers, street signs pierced with bullet holes, and damaged plaques commemorating the « Heavenly hundred », the fallen protesters killed in Kyiv’s street during the Maidan Revolution in February 2014. Belongings of ennemy soldiers reveal many things: they used road atlases from the 1970s to invade Ukraine, they wrote in diaries about their crimes and shared them with their relatives with no remorse, they also were sometimes quadruply vaccinated against Covid-19 with Sputnik shots.

Around this chaotic and chilling display from the get-go, the museum’s aisles are another display of the contemporary. Next to mosaics and painting replicas of the Tithe and St Sophia churches, exhibitions show Ukraine interrupted in its identity quest. Because “in a museum as in life, ugliness and beauty coexist side by side”, dresses from acclaimed fashion designer Serhiy Yermakov are on show just next to a retrospective on weaponry used by Ukraine to defend its territory. Next to javelins from the 5th century BCE, cossack mases and spears from the 16th-17th centuries, and small weaponry used by nationalist groups of the beginning of the 20th century, a window reminds the visitor that blood continues to flow in what historian Timothy Snyder called a bloodland: there, pictures of the museum’s employees who joined the Ukrainian army last year are displayed. All pictures show men and women in their fatigues, and short biographies attest that this war is very much that of civilians having taken up the arms. Like in 1914, they too fight in muddy trenches, and witness the butchery.

There is Volodymyr Kolybenko, director of the Ancient History department, and Oleksandr Khomenko, director of the section devoted to the short-lived Ukrainian Republic of 1917-1921. His broken glasses are exhibited too. Anatolii Barannik and Karine Kotova, senior researchers, technician Volodymyr Kruchok, engineer Hryhorii Buhaiets, and the museum’s janitor, Viktor Vovk, is also there. Those are no longer the keepers of a history displayed behind glasses. They are the safeguard of their country’s independence.

In the upper floors, the presence of war overflows even the staircase, where suspended shrapnels and explosive devices overlook a map drawn on the floor.

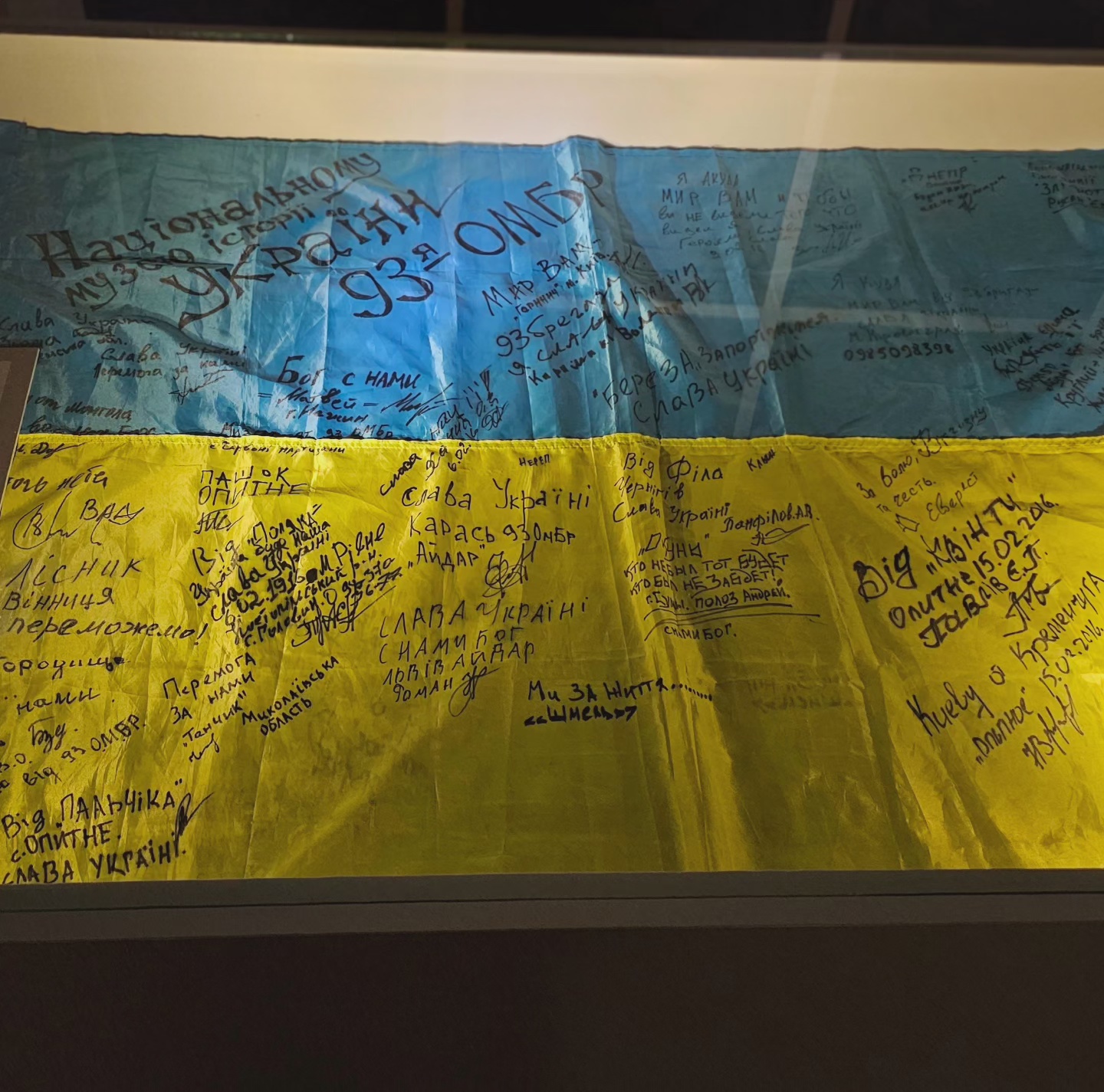

One floor up and the metallic grey is replaced by a flow of blue and yellow colours. Here, the Ukrainian flag is on display. That flag represents the fertile soil and the glorious sky, symbols of independence and freedom. Washed out but majestuous, there are two giant flags flown over public buildings in Kyiv and Lviv in 1990, during the fall of the USSR, next to a mosaic of pictures showing the flag in all its states, and during various events that shaped Ukraine’s history. To those of polar expeditions and Eurovision song contexts, are added the flag soaked in the blood of Nazaziy Voitovych, a 17 year olf student from Ternopil killed in February 2014 when he came to Kyiv to protest against the corrupt pro-Russian regime, and the flag signed by the mythical brigade 93, who defended Donetsk Airport for months during the Second Battle there, despite being under siege and attack until the beginning of 2015 and the fall of Donetsk.

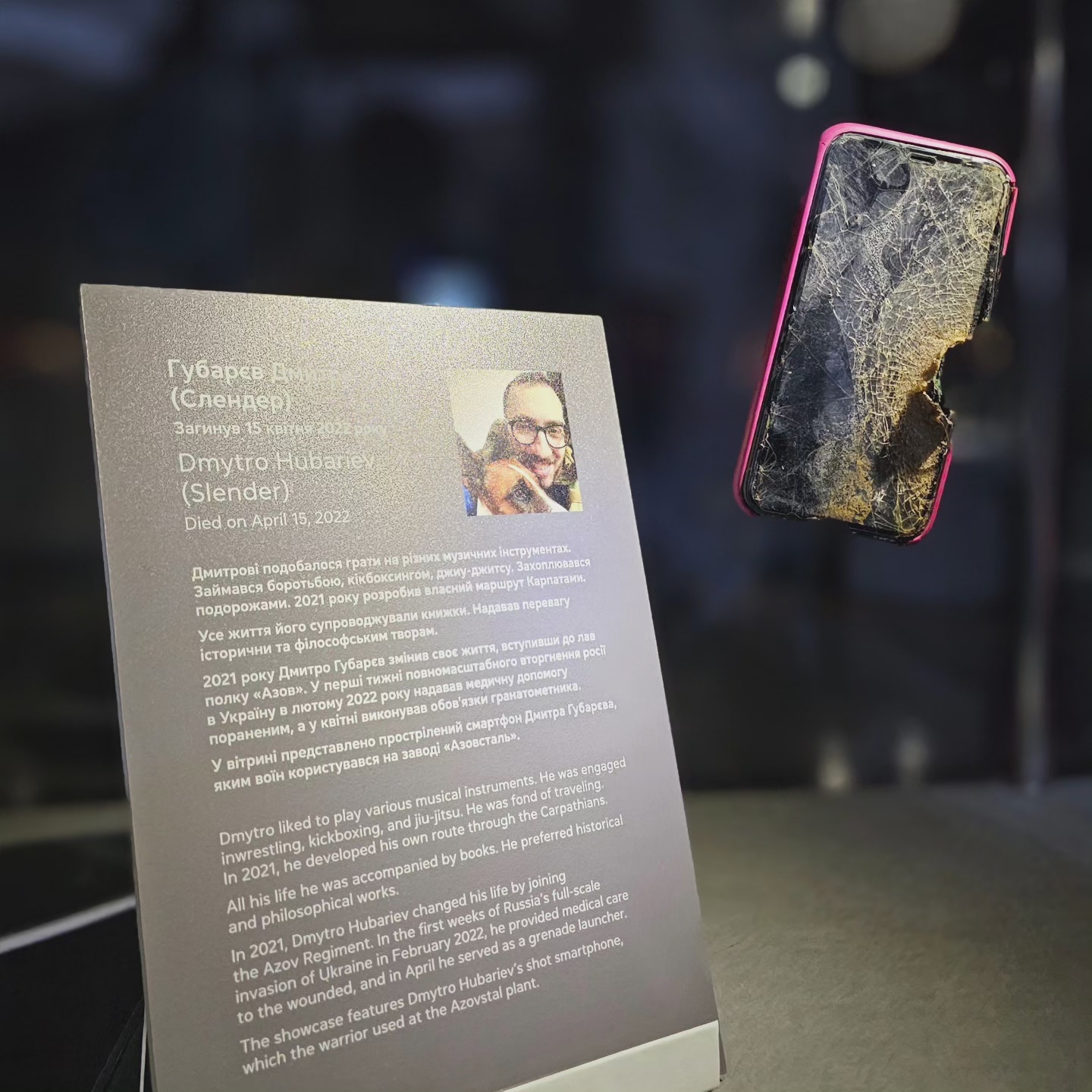

The colours of the flag stand in sharp contrast with the darkness that engulfs the museum’s last floor. There, it is time for contemplation. This is where the fight and resistance of the Azov Bataillon in Mariupol are recollected. Right at the entrance, the sight is dizzying: on four walls, lines upon lines of names and pictures remind ad infinitum the price paid by Ukrainians in the war. Mostly men, mostly young, in any case too young to not live. Candles and flowers show the grief of the hundreds of families mourning one of theirs.

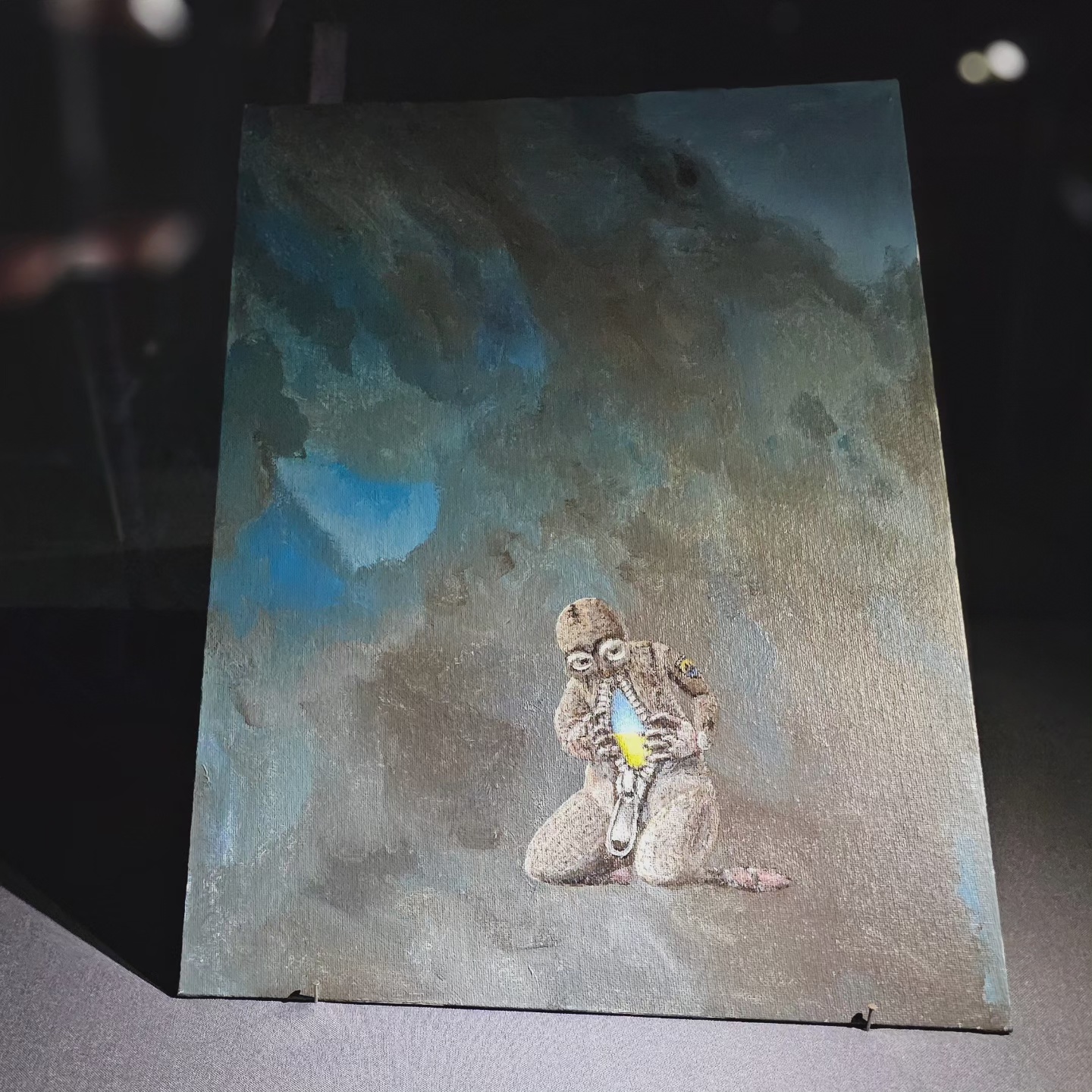

Finally, in the shadows, the history of the Azovstal factory is punctuated by lightshafts, in which belongings of fallen soldiers remind the humanity of those who died for their land. A set of figurine knights belonging to Denys Dudinov, namecode “Ghost”, the second of two brothers who died on the frontline, in his native Donetsk region, a drawing from Stanislas Kovshar, namecode “Bard”, the smashed phone of Dmytro Hubraiev, namecode “Slender”. Medals, boxing gloves, pairs of shoes…all are signs of lives interrupted by the Russian agression.

While the Ukrainian governement refuses, and will likely continue to do so for the duration of the war, to communicate on the number of dead on the frontline, the Museum of History displays, without any figure being necessary, the very grave significance of the human losses for generations to come. Walking through the exhibitions, the visitor can only try and understand, through past and present events, the current cycle of events. In the museum as in everyday life in Ukraine, there is no way to escape war.