Podil was hit badly two nights ago, it was the second night in a row that we had been having strikes in the city center. Considering, anybody living in the heart of Kyiv is very privileged: we can enjoy a relatively normal life most of the time. Except when Russia strikes.

The following day, when I asked my friend Katya, who lives in that district, if she was ok, she told me that everything was fine with her. I was dealing with my own trauma that day, reporting on the death of two journalists, murdered by Russia with a drone, in Kramatorsk, a city I know well, a city which I know faces the same fate as too many others in Donbas before: Chasiv Yar, Pokrovsk, Toretsk, which you, reading me in English, might know only through pictures of their utter devastation. But those places didn’t use to be ashes, they used to be full of flowers, and full of life, until Russia came and levelled them to the ground.

So after reporting on the death of Olena Gramova and Yevhen Karmazin, I felt nothing but emptiness. Somehow, this particular murder hit me, my hands were shaking uncontrollably. I didn’t know them personally, I knew them through their work. I shelved the ton of reports I was supposed to hand in because I simply could not think, let alone write. I watched one of their reports, embedded with an NGO evacuating civilians in Donbas, something they filmed in March this year. Under Russian attack, they follow an NGO in Kostyantinivka now evacuated hospital. I can’t help but cry when I see that this video got a little more than a thousand views since its publication in March. Those are colleagues who day in, day out, risked their lives on the ground, close to the red zone, to report on Russia’s crimes against Ukraine.

But back to Kyiv. Today I was chatting to Katya’s sister, on a completely different topic (namely, why does a Kramatorsk hospital still invest in a 5 million hryvnias top-notch new X-ray machine when the city is being bombed daily and whether this will ever make sense), and she let slip that she is very stressed out “given what happened to Katya”. Follows a moment of confusion, what have I missed? It turns out that Katya’s building got hit with shrapnel that night. I write back to Katya. “and you told me you were fine?!”. She answers “well, I’m fine, and the windows shattered were on the other side of the building, and I’m alive, so, considering, yes I’m fine”. I’m both relieved and appalled. This is neither fine nor normal, yet it is our reality.

This week, on October 20th, 84-year-old Larysa Vakuliuk, a goat herder from Kherson region, got targeted and killed, alongside her two goats, on a country road by a Russian FPV drone. It will never be said enough: FPV, First Person View, means that the pilot sees very well what, or who, he is targeting. Larysa had refused to leave her home, because she didn’t want to abandon her animals.

In Chernihiv region, half of the population was plunged in a full blackout and emergency tents, “invicibility points”, had to be set up.

On October 22nd, in Kyiv region, Antonina Zaichenko, her six months old baby girl, Adelina were killed, alongside her 12 year old niece Anastasiia. The family had moved from Kyiv to the village of Pohreby, in Kyiv region, as they thought this would be safer.

The same day, October 22nd, Russia launched a kamikaze drone on a kindergarten in Kharkiv. The 48 children present were apparently uninjured, but one man died, one person lost a leg (authorities communicated on a “traumatic injury resulting in amputation”, and another person suffered burns on 20% of their body”).

Back in Kherson, on October 24th, Russia also attacked the city with a multiple launch rocket system, resulting in three deaths and at least 14 injuries, and in Odesa region, Russia launched glide bombs, a first in this part of Ukraine.

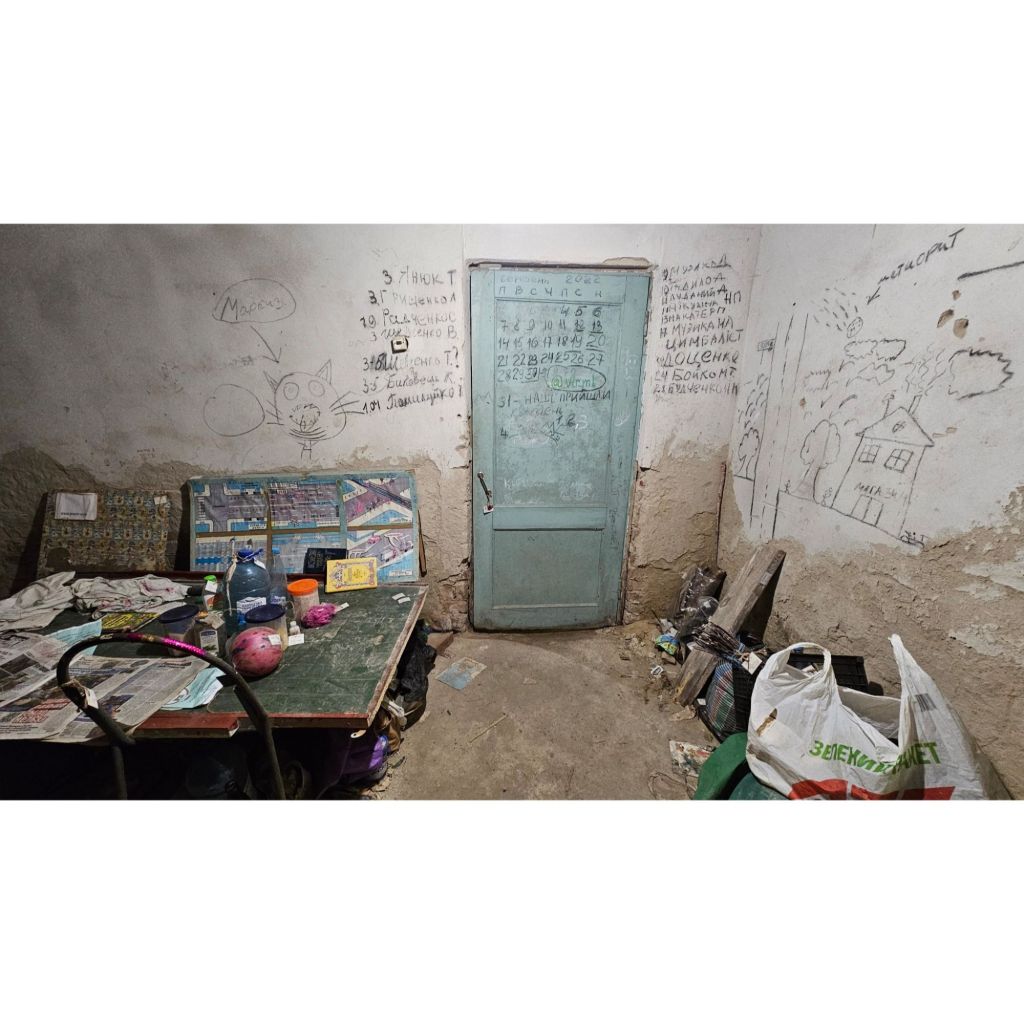

This week, the numbing sound of diesel generators roar in most streets in Kyiv. It is deafening. Many shops, cafes and restaurants are plunged in obscurity. It is dark and cold, I am writing those lines wrapped in my coat, with the desk light flickering, and all my electric devices are charging, just in case. In the corridor, I have lined up water supplies, in case Russia hits again and deprives us from running water. Next to the bottles, a fire extinguisher, in case a drone, or worse, a missile, hits the building. A bag with my important documents and the cat transport boxes are ready to be grabbed in case I have to leave the flat in a hurry.

I am lucky to live in the safest area of Kyiv, a European capital which still shines in many ways, except not at night because now it’s mostly plunged in an unwelcoming darkness, and it does not feel safe anymore. As I am writing those lines, I ask myself, am I fine? I am, because I am alive and I still have all my limbs. My loved ones are alive. I get to write these lines. This is what we consider fine here. But if I answer the question “are Ukrainians fine?” (which they can answer themselves, please, please ask them directly), I would say, no, Ukrainians are not fine, they are surviving, although like every other being, they deserve to live safely, instead of seeing their country being ripped apart daily.