The Kyiv–Kramatorsk train can’t run up to its final destination anymore. The final stops of Sloviansk and Kramatorsk have become too dangerous, as Russia now targets railway infrastructure all along the frontline.

I was on board this train often, and each time, it was an important lesson in what this war is about.

What is that journey about? A Kyiv-Kramatorsk journey begins very early, with an alarm clock ringing at 5 a.m., and a race to Kyiv’s main station to catch the Kramatorsk-bound train which departs, still, at 6:44 in the morning, sharp, no matter what. At dawn, hundreds of people with red eyes—from crying, from exhaustion after a night of Russian air raids—hop on or say goodbye to their cherished relatives who are going on board.

It is called the “Love train” because it links families to their loved ones, from across the country, from the rear to the frontline, soldiers with their lives, in many ways. It is a war train. On the racks, camouflage bags in all shades of green show the presence of servicemen returning from permission. Chevrons show legendary brigades fighting in the direction of Lyman, Kostyantynivka, and Pokrovsk.

As the train departs, the sun rises and basks the statue of Mother Ukraine in a beautiful pink light, or wraps her up in a fog, depending on the weather. The train lulls us away from the capital. It is quiet, apart from the back and forth of the coffee-trolley that circulates across our carriages.

At 9 a.m. sharp, the daily minute of silence and the stern countdown in memory of all the people who gave their lives defending Ukraine plunges each carriage into an atmosphere of deep and quiet reflection. Some people stand, others just bow their heads. In Ukraine, everybody knows in their flesh the price of blood paid for the country to remain free.

On board, everybody is involved in the war: humanitarians, journalists, soldiers, and their families. Yet it is a train full of life: each ride brought back home dozens of people uprooted from Donbas and coming back to visit their relatives left behind, a handful of humanitarians, and dozens of wives, girlfriends, and children of soldiers.

Riding this train, slowly heading towards Donbas, through the hills of Poltava and the vast fields of Kharkiv Oblast, is a travel through Ukraine’s rich landscapes and a travel through its history.

The closer one gets to Donbas, the more visible the war becomes. As the scenery passes by the window, it fills with ever more grey, dark green, and all shades of military vehicles that drive towards or come back from the frontline.

There are scenes of ordinary lives: babusias on their bicycles, mothers in pink hoodies walking their toddlers.

Then there is the Ukrzaliznytsia message upon arriving in Kramatorsk: “Thank you for your support. Our trains are getting ready to return to Donetsk, Luhansk… see you soon on Ukrainian railways.”

Each time, arriving in Kramatorsk felt like it could be the last. Earlier this summer, seeing the Lozova station in ruins foreboded the worst: it was only a matter of time until the Kyiv–Kramatorsk would stop running up until its final stations.

At each station, emotional reunions of families and lovers took place on the platform. But the most moving of all happened in Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, as the train finally came to a stop and the doors opened. At this moment, time stopped. We all knew one has to walk away from the station as quickly as possible, as it is Russia’s target of choice. Yet, time stopped right here. Tired but happy-looking men in military clothes, of all ages, welcomed their wives, fiancées, and girlfriends with tight embraces that let all their exhaustion and relief transpire. So many tears, most of happiness. Each hug is a victory against the aggressor. Each reunion a blessing for one soldier and his family.

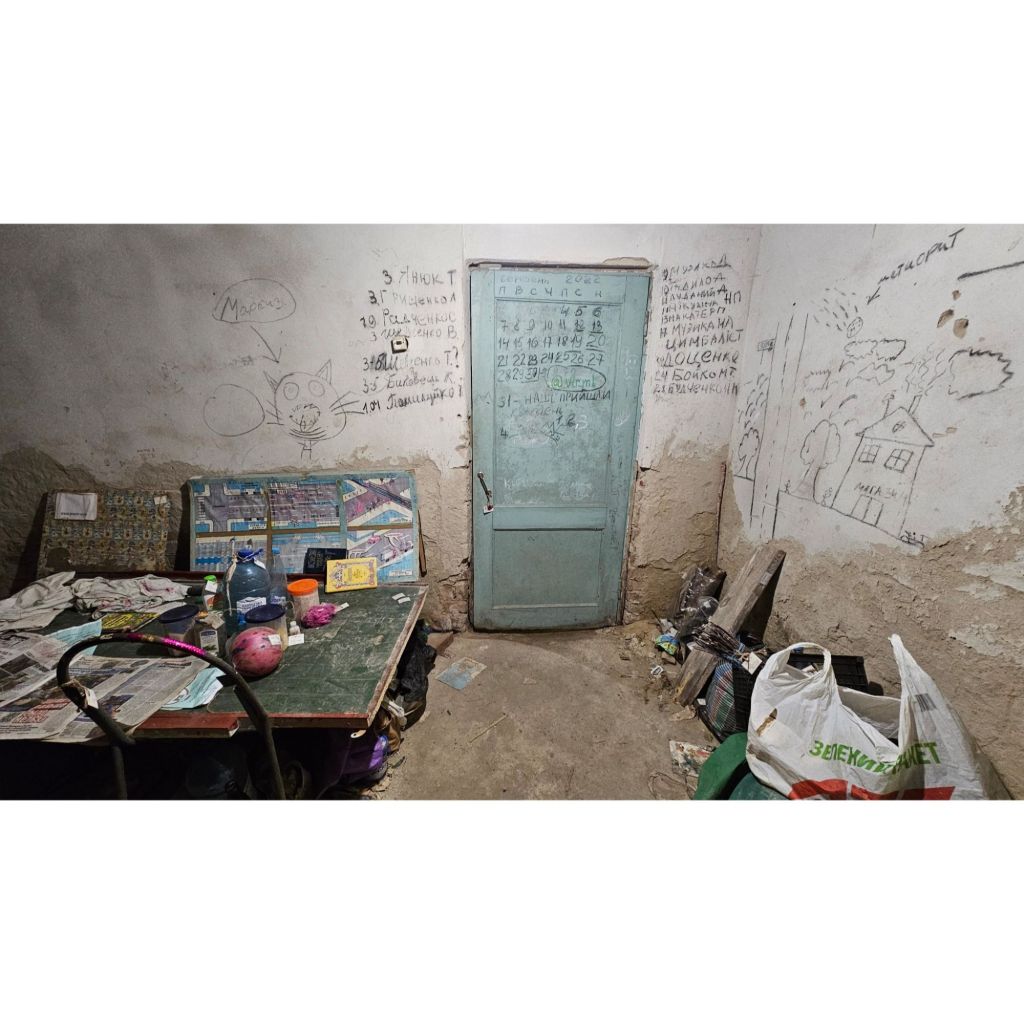

Finally, love. Finally, this long-awaited hug. Love, through blood and sweat, and the smell of Ukraine’s soil and its hundreds of posadkas, the hiding lairs where tens of thousands of Ukrainians shelter along the frontline.

Love, the only thing that still makes sense. The one thing everybody fights for. This love persists, despite all this blood, all this misery, all this horror. All those killer drones.

The Love train no longer brings together lovers on Kramatorsk’s platforms. It is a tragedy. It was a handy commodity for thousands of customers.

But to think that love can be stopped because of the aggressor would be to grossly underestimate what Ukrainians are capable of—what love is capable of.

Life will be tougher for soldiers in that sector; travel will become even more uneasy.

But there will be other routes. There will be other reunions. And there will be love, always.